Some quick thoughts on learning compressed representations and GPT-5 speculation

Language models are impressive, but I think they are cheating. We give them an abstract vocabulary as a way to compress the external world into a manageable set of 50,257 tokens. Since (almost) any human can understand sequences of these tokens, our compression scheme must have been effective enough to distil a key chunk of our understanding of the world into an abstract vocabulary.

Two lemmas

Real-world intelligence obviously doesn’t require the use of language as a compression tool. The common example is cats — much more “intelligent” in terms of planning than any current LLM would be in the real world, and they don’t speak a lick of English. So if you want to take in all the data that humans do every second of our waking day, from visual to audio to sensory, you can’t cleanly and efficiently represent that data in language. The key point here is that we have no abstract language over these high-dimensional input spaces that make up the real world. That’s the first lemma.

The second lemma is that (subject to current orders of magnitude of compute) we have no way of efficiently predicting or learning meaningful representations of these high-dimensional spaces. The strongest evidence here is probably JEPA — after many years of experiments, even Yann Lecun couldn’t manage to get an efficient predictive model in the original high-dimensional space. This, by deduction, means that we must learn representations in some compressed, latent space, and do our predictions there.

Computing compressed representations for transformers

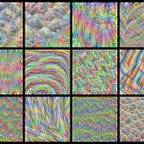

So how do we go about computing these compressed representations? Of course, you could use any old autoencoder. However, if we’re talking about transformers, then you need discrete representations (or at least, it certainly helps). This means you probably want something like a VQ-VAE (or improved versions like finite scalar quantisation). You take in some massive high dimensional vector space, learn an abstract vocabulary of “tokens” corresponding to codes in the VQ-VAE, and use a transformer to do prediction over these tokens, and then decode the final sequence back to the high-dimensional space with the decoder from the VQ-VAE. I’m pretty sure this is roughly what OpenAI’s SORA is doing with its “patches” for video generation, but I haven’t read the technical report yet.

A prediction for GPT-5

A perhaps non-obvious implication of the above reasoning process is that you don’t just have to have one abstract vocabulary. What if you had multiple levels of abstraction, each with its own vocabulary? The higher up the level of abstraction you go, the less tokens you have and the bigger the “concept” an individual token represents.

Then, you condition on some reward or end state (which transformers are very good at — see decision transformer) and do autoregressive prediction over the highest level of tokens. Then you use a transformer trained on the vocabulary one rung lower on the ladder of abstraction to “decode” these tokens into its own vocabulary. Then you repeat until you get down to our original language (i.e. GPT-4).

I think GPT-4.5 / GPT-5 will be something like this. In reality, it will probably have one high-level planning transformer that does prediction over abstract tokens. These abstract tokens can be learned by simply applying a VQ-VAE to our current corpus of tokenised training data. Then, the high-level generates the whole “sequence” in these abstract tokens, perhaps with some sort of beam search or Q* to determine the best possible paths (this in my mind corresponds to planning). Then, the lower level transformer (i.e. GPT-4) just does what it does best, except conditional on this high-level plan. This overcomes the limitation of our current GPT models: they can’t plan. Once they make a mistake, for instance, it’s hard to go back and correct oneself.

How do I get involved at home

Without a cluster of H100s it’s probably difficult to get in on any of this action. However, I’d currently look at:

- Creating multiple levels of abstraction over language by controlling the number of codes in a vocabulary learnt by a VQ-VAE. Can we compress chunks of 256 tokens down to 128, 64, 32, 16, even 8?

- Should we have use variable length sequences to compress certain sequences down? This makes the most sense — there’s no direct mapping between the original sequence length and how many abstract concepts it contains.

- What if we just learn a VQ-VAE over Matryoshka embeddings? You could cut off at various lengths and learn the vocabulary this way.

- Create small algorithmic pixelated videos and see if various levels of abstraction can capture the dynamics of the video.